Movies

The Ugly Truth

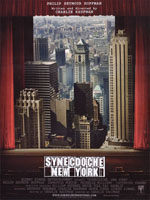

When Caden Cotard wakes up, the first thing he does is look in a mirror. He sees a pudgy, middle-aged, balding, sad-sack of a human being. The rest of the movie will be like that: a merciless self-examination. Neil Gaiman, sci-fi and fantasy author, described most current literary fiction as “miserable people having small epiphanies of misery.” Charlie Kaufman, who wrote Being John Malkovich and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and who has written and directed Synecdoche, New York, is more ambitious, intelligent and talented than the majority of his contemporaries, but the effect is the same: a numbing sense of despair and hopelessness alleviated by brief bits of gallows humor. You might describe it as miserable people having surreal epiphanies of misery.

That’s not to say that there aren’t rewards. Like the reality-bending labyrinth that was David Lynch’s Inland Empire, Charlie Kaufman’s art world is insular and challenging, tedious and moving, held together by the power of its lead performance. Philip Seymour Hoffman offers an unsentimental, subtle portrait of Cotard, a theater director who has come to confuse theater-going with navel-gazing. Kaufman attempts to define the universal with the particular by showing us the tenuous choices, unrealized dreams, missed chances, regrets, and heartache in the life of one man whose magnum opus is a play about his own life. But Kaufman’s (or at least Cotard’s) world is death, decay, illness, pessimism, disappointment, brutality. “Nasty, brutish, and short,” as Thomas Hobbes so memorably put it. Thankfully, that worldview does not apply to everyone, even to those in circumstances that would merit it. Cotard demands of his cast and crew: “I want the brutal truth. Brutal. Brutal.” But the truth would not be so brutal if Cotard did not insist on its brutality. Contemporary art, like Cotard’s decades-long project, is obsessively self-referential, continually asking, “who am I”? The answer to that question, without reference to Goodness or Beauty, is indeed an ugly Truth.

By AT 10.29.09 05:02AM Not Rated

Interesting parallel here with the dark night of the soul. Might this play embody the angst of post-Christian Western culture, whose rootedness in God is now obfuscated by obsession with the empty promises of materialism? Without the light and i-Thou relationship of faith, artistic musing on life all too easily becomes a nihilistic lament, much like that of Qoheleth, the Philosopher of Ecclesiastes: “Vanity, vanity; all is vanity…”

The author insightfully notes:

“Contemporary art, like Cotard’s decades-long project, is obsessively self-referential, continually asking, “who am I”? The answer to that question, without reference to Goodness or Beauty, is indeed an ugly Truth.”

Perhaps like Mother Teresa in the depths of her own dark night, we need to collectively taste the bitter finite emptiness of our obsessive self-reference, in order that we might once again open ourselves to Truth whose beauty can provide us with a reference point outside, yet deep within our being - that we are unconditionally loved by Love.

By cartesian coordinates AT 12.23.08 03:48AM Not Rated

“Kaufman’s (or at least Cotard’s) world is death, decay, illness, pessimism, disappointment, brutality.” Was this movie based on a Philip Roth novel?