Politics

What the Presidential Election Reveals About the American Soul

With the death this week of Chiara Lubich, founder of the Focolare movement, the passing of the generation that founded the lay movements and greatly influenced Vatican II is accelerating. St. Josemaria Escriva, founder of Opus Dei, died in 1975, and Servant of God Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker movement, died in 1980. Within the past three years, three founders—Msgr. Luigi Giussani (Communion & Liberation), Fr. Marcial Maciel (Regnum Christi), and now Lubich—have passed away.

Lay or “ecclesial” movements are the Church’s best kept secret. In simple terms, they’re like religious orders, except that they’re designed for lay people, and their members are committed to living their faith in “the world.”

With the passing of their founders, some people are asking how enduring these movements will be. For some, like the Vatican observer John Allen, the movements are a very specific response to secularization and the collapse of parish life in Europe, with limited relevance to the U.S.

For others, myself included, they’re the leading edge of the Church’s mission ad gentes—to the nations—especially the U.S., and they’re doing for the Church in the twenty-first century what the newly formed Franciscan and Dominican orders did in the thirteenth century. When people talk about the role of “creative minorities” in sustaining the life of the Church, in many cases they’re referring to these movements (Disclaimer: I am not officially a member of any lay movement).

A great example of a creative minority at work was an event last Wednesday at Columbia Law School in New York, organized by Communion & Liberation—known as “CL”—a panel discussion with the provocative title: Forward Together: What the Presidential Campaign Is Revealing about the State of the American Soul.

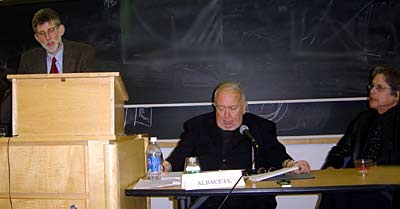

The discussion, part of CL’s Crossroads Cultural Center, brought together two journalists from opposite sides of the political spectrum—Marvin Olasky, editor of World Magazine, from the right, and Hendrik Hertzberg, executive editor of The New Yorker, from the left.

The moderator was CL’s national director, Msgr. Lorenzo Albacete, widely considered the most authoritative and provocative Catholic commentator operating within secular media today. (For example, when PBS did a documentary on “Faith and 9/11,” they gave Albacete the closing remarks). Albacete’s unique achievement is that he’s equally respected both inside and outside the Church. He’s managed this by combining a mordant wit with mystical wisdom—and perfect comic timing. When Hertzberg opened his remarks by explaining that while he didn’t believe in God, he believed in Albacete, the monsignor immediately intoned, in his baritone: “Good enough.” It brought the house down.

The motive for bringing Olasky and Hertzberg together was not to conduct an argument between left and right. As one of the event organizers, Carlo Lancellotti explained to me, “Reality is an event, not an idea.” The point was to have an encounter where the role of faith and reason in public life could be explored in friendship. “There is a cultural vacuum” in our society, Lancellotti added. “Politics alone cannot sustain the life of a people. By raising the question of human desire, we can make a contribution.”

On the deepest level, this sort of event, for CL, is always worthwhile, because a human encounter between opposing sides happens, and who knows where it will lead? But on the surface, based on their speeches and answers to questions, Olasky and Hertzberg seemed entrenched in their positions, and either unable or unwilling to explain their viewpoints in terms of faith and reason. Instead, we seemed to be getting a preview of what could be a very polarized general election.

Of the two, Hertzberg was the more ideological. That’s understandable. After almost eight years of George Bush, liberals feel a strong sense of outrage about a range of issues, including the Iraq war, the divide between rich and poor, and torture. They feel they’re ascendant, that it’s their election to lose. More important, they feel like they have the moral high ground as well. Hertzberg hit back hard against the charge that liberals are moral relativists. What you could hear in his voice was a preview of “Obama the moralist” this November, making the case that whether as Christians, or atheists, liberals have values that are as strong, if not stronger, than the values of conservatives.

Conversely, Olasky was more tentative. As a sincere Christian, he was clearly on the defensive trying to defend the policies of a party whose president is widely perceived as being on the wrong side of the issues cited above. To his credit, he did a much better job of objectively analyzing the role of faith in the election, parsing the two most religious candidates—Mike Huckabee and Barack Obama—through the ideas of Alexis de Tocqueville, and examining the role in the election of what he called the 4 Rs – religion, restlessness, reality-based, and rambuctiousness.

The first, religion, is self-explanatory. Despite the weakness of the Christian Right, the irony is that the role of religion has actually expanded in this election, with every candidate forced to account for the role of faith in his or her life.

About the second R, restlessness, Olasky said, “all three candidates have turned “change” into an applause line. That’s strange. Why, when America is the most affluent society in history, is “change” a plus?” He connected this point about change to Obama’s Christian messianism, the strongest since Wiliam Jennings Bryan ran for President at the start of the 20th century.

In regard to the 3rd R, “reality-based,” Olasky cautioned that despite the appeal of Obama’s messianism, in the end Americans are a practical people. This explains why Bryan lost three times. The 4th R—rambunctious—has to do with how bloggers, talk radio, and other grassroots media have kept the candidates, and the mainstream media, honest. (You can find Olasky’s articles on the 4 Rs here).

The most interesting part of the evening came after Olasky and Hertzberg spoke. Msgr. Albacete posed a question to each speaker, probing particular weaknesses in the conservative and liberal positions:

To Olasky: “Why is it that the Christian presence in U.S. politics always ends up moralizing, while at the same time the individualism of the culture goes unchallenged? Are conservatives making a real cultural proposal or just reacting to the other side?”

To Hertzberg: “Liberals are especially concerned about education, but they refuse to accept any shared content (except “science”) for such education. How can this not lead to a progressive impoverishment of the public discourse?”

Both Olasky and Hertzberg genuinely seemed to miss the point of the questions. Olasky didn’t see why individualism would pose a problem for a Christian culture, and Hertzberg didn’t see how omitting a sense of objective truth might pose a problem for liberal education.

The discussion went back and forth for a short while, with a few interesting flashpoints. Msgr. Albacete asked Hertzberg how it’s possible to condemn torture without recourse to substantive values. When Hertzberg objected that the supernatural didn’t enter into it for him, Albacete explained that he wasn’t referring to the supernatural, but to reason. Hertzberg wasn’t having any of it, remarking that reason was just “backfill”— “people take positions and then find reasons to justify them.”

Towards the end, one person turned to me and said: “There are no self-evident truths anymore.”

As Lancellotti elaborated to me after the event, political debate “always goes straight to morality. Truth is always moral truth, about right and wrong. Philosophy is bypassed. So how do you talk to an atheist? Yes, we have revelation, but how do you communicate truth to a non-believer?”

For me, the event gave me hope that despite the frustrating political situation, “creative minorities” in the Church are doing something positive—or rather, “being” something positive—creating islands of charity where faith and reason are lived, in communion with others. It’s not a grand solution (which would just be utopian dreaming anyway). But as Mother Teresa said, small things done with love have infinite value. Even in politics.

By AT 03.17.08 03:56PM Not Rated

Hi Liberty_student37,

I’m glad you have found a place in the church. I think that’s the beauty of the diversity and depth of Catholic spirituality. It does not offer just a single, one-size-fits-all spirituality.

But I lack perspective. Would you be willing to share what it is that causes you to doubt that you would still be catholic. I ask solely out of a sincere desire to understand. You can send me a message directly if you’d prefer.

Sincerely,

Eric

By AT 03.19.08 01:29AM Not Rated

It does not offer just a single, one-size-fits-all spirituality.

Lorenzo Albacete has a great sense of this. Have you seen him on video?

By AT 04.10.08 01:49AM Not Rated

I’ve come to the party a tad late here, but just wanted to add my two bits. A friend of mine (now a priest) cited Albacete as one of the primary forces behind his conversion. Referring to Albacete, he told me that “to deny Christ would be to deny this man.”

In some ways that’s the logical extension of Hertzberg’s comment that he didn’t believe in God, but he believed in Albacete. The Msgr’s “Good enough” retort is classic, of course, but I think my friend’s insight was more profound than Hertzberg’s: we encounter Christ in our relationships with others. To deny Christ would be to deny Albacete, and to deny Albacete is to deny his sense of the world, which is joyfully infused by Christ’s message.

By liberty_student37 AT 03.17.08 09:36AM Not Rated

Chesterton, in his book “The Catholic Church and Conversion,” talks about converts after coming home to the catholic church tend to struggle staying catholic. I know that’s the case for me because I’ve only been catholic for a year (this easter vigil) and if it wasn’t for Lorenzo Albacete and CL I don’t know if I’d still be catholic.

These ecclesial movements are really just amazing.