Faith

Doubting Doubting Thomas

Go to Chennai in south-east India, a humid city of car manufacturers and computer whizzkids. Chudder out of town in a tuk-tuk motorised rickshaw – weaving, heart in your mouth, between motorcycles balancing entire families and their babies - to the Mount of St Thomas.

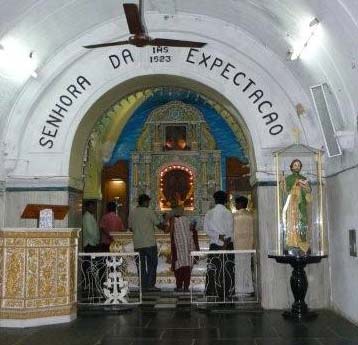

Climb the hundreds of steps to the place where the apostle was speared to death in 72 AD. Leave your shoes outside the little Portuguese chapel, which sits atop a rare elevation above the coastal plain. Pray a while before the stone cross the apostle carved, which used to bleed some centuries ago.

Ponder his story. And ask yourself if it’s fair, this idea of St Thomas as a “doubter”.

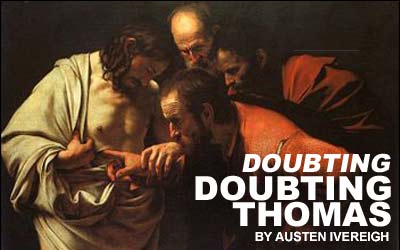

For the common assumption is that Thomas was a kind of Englishman: sceptical, empirical, hesitant. The image was struck after he missed Jesus’ first resurrected appearance (he was shopping at the time) and demanded physical evidence before he could accept it. Jesus came again, obliging him, and Thomas “believed” – but “affirmed” would be more apt. The patron saint of sceptics was born at that moment, as was his name, a combination of theos (God) and meus (my), from the great statement that issued from him—“My Lord and my God” —after he touched the risen Jesus’s wounds.

But was Thomas really a sceptic? Consider his appearances earlier in John’s Gospel. When Jesus makes off to bring Lazarus back from the dead, an act which his followers know will fast-forward his brutal execution, Thomas tells them, in what must be the least whimpish utterance of Jesus’ followers anywhere in the Gospel, “Let us go also to die with him”. Where the other disciples flip-flopped, Thomas was heroically steadfast.

True, he needed clear directions. When, in John 14, Jesus tells his disciples: “Where I am going you know the way”, Thomas reacts testily. “Master, we do not know where you are going; how can we know the way?” He wants signposts. He likes a map. He needs the orders spelled out.

We all know the irritable (and irritating) type: “Just tell me clearly what you want me to do, and I’ll do it.”

But that does not make him a doubter.

It occurs to me, following the steps of the apostle in Chennai ( which used to be called Madras until the Tamil Nadu nationalists changed the name in the 1980s), that Thomas’s evangelizing journeys after the Pentecost, culminating in his brutal death, tell a quite different story from the role he has been cast in the Christian script.

There is an instructive tale told in the medieval book of the saints compiled by Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend. Thomas, says de Voragine, was in Caesarea when the Lord appeared to him to tell him that Gudnaphar, the King of Punjab, had sent his provost to look for a man skilled in architecture who could build him a palace in the Roman style. “You’d be perfect,” says Jesus (actually: “Come along, and I will send you with him”). Thomas, still happy to quiz his Master, answered in words that many missionaries and diplomats must have said to their superiors over the ages: “Lord, send me anywhere but India”. Jesus assured him he would be safe until “you shall come to me with the palm of martyrdom”. Thomas, as always, agrees: “Your will be done”.

The apostles included a money-lender and a doctor; why not an architect? Thomas, by accounts a skilled carpenter, would have known how to design structures. The role fits the personality. Builders of houses like their lines drawn straight; they thrive on plans.

So Thomas is introduced to the King’s provost and the two set sail for a city in what is today probably Pakistan. At the court of Gudnaphar Thomas drew up plans for a magnificent palace, and the King gave him a large sum of money to build it. The king then left for a two-year visitation of another province; in his absence Thomas shared the king’s money among the poor while evangelising and converting with great success.

When the King returned, Thomas told him he had used the money to build him a great palace in heaven. Gudnaphar, unimpressed, imprisoned the apostle, with orders to flay him and burn him alive.

But then the King’s brother, Gad, fell ill and died. On the fourth day he came back to life after having had a vision of Thomas’s celestial palace. The king set Thomas free, and fell at his feet.

The apostle arrived on the Arabian sea coast in AD 52. Now just a village, Palayoor was then a major trading post, where merchants came from Rome and China to deal in pearls, silks and spices; there was a substantial Jewish colony there, and Thomas settled among them. He preached the Gospel for a year, baptising a thousand Hindu converts, before travelling south to Malabar. Here, among the villages of the balmy, palm-fringed coconut coast of what is today southern Kerala, he spent 14 years, founding the seven churches from which today’s Syrian and other Indian Christians, mostly Catholics, are descended.

Then he upped anchor for the last time, travelling across the mountains to the Coromandel Coast, on the shores of the Bay of Bengal, to Myalapore which is today part of Chennai.

Timorous types would hardly choose, as Thomas did, to encourage the King of Myalapore’s sister-in-law, Migdominia, to opt for virginity. (The queen later became convinced to do the same). But the cause of Thomas’s death, according to the Golden Legend, was the apostle commanding a demon lurking inside an idol to destroy it. When the idol “melted like wax”, de Voragine narrates, “all the priests bellowed like cattle, and the high priest of the temple, raising his sword, drove it through the apostle”. The king and his brother, “seeing that the people wished to avenge the apostle and burn the high priest alive”, fled. The Christians carried away the saint and buried him in Myalapore.

There is another, more official but duller, version. While at prayer on a mount, the one where his shrine is today, a Brahmin surprised him with a spear, dealt him a fatal blow, and Thomas went to the multi-roomed mansion prepared for him.

Whichever version you believe, his was the death of a martyr, not a fence-sitter; his the fate of those who dare to confront idols and the social arrangements which they support. His flourishing mission, and the Gospel he preached, was a threat to the position of the Brahmins, who drove him out from the court and killed him. If Thomas was the nervy type, he disguised it well.

The church of San Thome, where the apostle is buried by the sea, was described by English pilgrims sent by King Alfred in 883, and later by Marco Polo in the thirteenth century. When the Portuguese arrived in the sixteenth century, they rebuilt it. Today it is one of three basilicas – the others are St Peter’s in Rome and St James in Compostela – erected over the body of an apostle. It survived the 2004 tsunami, locals say, because of that presence; the water destroyed much that surrounded the basilica.

After Easter Sunday Mass there, I dropped underneath the altar to where an encased plaster effigy covers the body long since dismembered by pious pilgrims. There he lies: serene, grey-bearded and handsome, the architect-missionary apostle who liked to know where he was going, but who never doubted who was leading him – even if he did not always like the manner in which he was being led.

Cardinal Newman once said that a thousand difficulties did not add up to a doubt. Thomas had difficulties trusting second-hand news, or imprecise directions. He was not like Peter, who relished a blind jump – even more if it included a triple somersault - and only later asked questions, usually when he landed on the wrong end. The so-called “doubting” apostle, on the other hand, liked to ask questions first, to make sure that when he jumped it was in the right direction. Where Peter’s courage often evaporated, Thomas’s never seemed to.

But did these difficulties – the queries, the hesitations, the architect’s plans—add up to a single doubt? Hardly. It seems unfair to depict Peter as courageous and Thomas as a doubter. His was a different sort of courage. He did not boldly go; he checked the route, then went boldly.

That is why “Doubting Thomas” sounds doubtful to me. “Planning Thomas”, perhaps?

I

By star AT 03.02.09 03:09PM

It’s not fair i believe, that our loving, faithful St. Thomas is called the ” doubting Thomas. ” Am sure it’s because of his profession, being an Architect that he planned his life with a laid out blueprint. That didn’t lessen his faith in our Lord Jesus! My dad, ( may he rest in peace ), was an Engineer and i know how he planned his family life. Everything for him, should be exact and sure, just like Mathematics is exact. He followed his own laid out blueprint in life, just like when he makes a blueprint for a project in the Public Highways. Witnessing my dad do that, i came to understand the character of St. Thomas. I guess, Theologians label St.Thomas as such, perhaps, not so much of the ” doubt “, but the lesson that they wanted to impart to us, that it’s ” blessed not to see but believed. ” St. Thomas, Pray for us! God bless!