Issues

Why the Bearded One is Right about Sharia Law

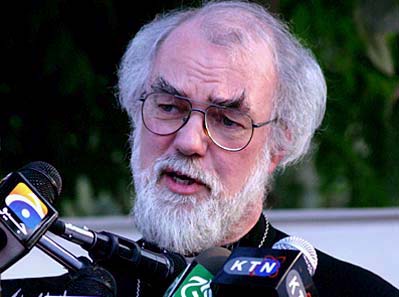

Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury, is an unusually courageous and thoughtful man, one of the few leaders in Britain willing to risk public outrage in order to point up uncomfortable truths. His lecture yesterday in the Royal Courts of Justice was exactly what is needed in the UK now: a challenge to the Positivism which is in gradual steps sweeping away the British tradition of pluralism.

The truth he gently points to is revealed in the reaction of British press and politicians. After he suggested that there should be accommodation of some parts of Islamic law within the British legal system, the Government moved immediately to stay clear of the tabloid garrotting machine. “British law should apply in this country, based on British values,” Prime Minister Gordon Browns spokesman quickly shot back, and others piled in. “The Archbishop should be standing up for the Judaeo-Christian values that underpin our laws” (a Tory Member of Parliament); “British citizens must be subject to British laws” (the shadow minister for community cohesion); “if Muslims want to live under Sharia law then they are free to emigrate to a country where Sharia law is already in operation” (a lobby called Christian Voice). And so on.

Hardly anyone, it seems, has actually read the entire lecture, or if they have, their eyes soon glazed over. It’s hardly suprising: Dr. Williams’s sentences are laden with subordinate clauses, and this was, after all, a juridical lecture given to jurists. But it was not muddled. It may need reading, and then re-reading. But what he says is clear.

He is not advocating allowing Muslims to opt out of British laws. He is not saying that Muslims should be allowed to be beholden to a system of law above the British state. He is simply saying that Muslims have a body of law which is already operative in the UK, just as Anglicans have ecclesiastical law and the Catholics have canon law, and Orthodox Jews have their own internal system. The last three are recognized by the state, but not the first. He is saying the time must come when Moslem law, too, is accommodated.

For the law to recognize a religious community’s internal methods of regulation is not to undermine or supplant the law of the land, because the law of the land applies equally to all. It is a parallel system. Catholics should be the first to grasp this. You can apply to the diocesan tribunal for an annulment of your marriage, and the tribunal may grant it on the grounds that the permanent sacramental bond of marriage has been entered invalidly. In other words, God does not require you to stay together. But that decision has no effect on the civil law. You retain the right to divorce, and all the rights that go with that, and to prevent misunderstandings, diocesan tribunals will not even look at your application until you have a civil divorce.

The parallels with canon law are very strong. As Dr. Williams says, Sharia is the practice of actualizing and applying the expression of the universal principles of Islam. Canon law is the attempt to implement, juridically, the universal teaching of the Church and Gods law expressed in Scripture.

To say that Sharia, when it is implemented, results in the stoning of adulterers and the cutting-off of wrists, is to say no little more than that canon law, in certain medieval and theocratic contexts, had results which would be abhorrent to contemporary mores. It does not mean that canon law is incompatible with human rights, only that when it becomes the law of the state it could be (think of the practical effects of excommunication in the early Middle Ages). The fact that there are Muslims who seek a literalist implementation of the laws of apostasy (stoning to death) in North Africa is not a reason not to recognize that among Muslims in the UK the Islamic Sharia Council is popular as a means for resolving marital disputes.

There may be conflicts with civil law areas of overlapping jurisdictions or incompatible concepts but it is for the jurists to work those out. Some may not admit of resolution. A Catholic priest in the UK has no right in law to keep what is said to him in the confessional private, but if he is asked in court to reveal something told to him in confession, he must still refuse and go to prison if necessary, because that is the only way he can be beholden to both canon and civil law. But the fact that this almost never happens is reason enough not to worry about it.

The basic principle is this. The recognition of some elements of Sharia over property inheritance, marital disputes and so on will not take away from the right of any Muslim to enforce civil law in these areas. Nor can Sharia law be enforced where it conflicts with civil law. Or in the Archbishop’s more elegant and exact phrase: “If any kind of plural jurisdiction is recognised, it would presumably have to be under the rubric that that no ‘supplementary’ jurisdiction could have the power to deny access to the rights granted to other citizens or to punish its members for claiming those rights.”

So much for the nonsense that fills todays British newspapers. But Dr. Williams’s speech is much more than just about Muslims and the law. What he is challenging is a Positivist, secularist notion of the law which seeks to make religious practice a purely private, individual matter. “The danger arises not only when there is an assumption on the religious side that membership of the community (belonging to the umma or the Church or whatever) is the only significant category, so that participation in other kinds of socio-political arrangement is a kind of betrayal,” he writes. “It also occurs when secular government assumes a monopoly in terms of defining public and political identity.”

The obvious recent example in the UK is one he cites earlier in the lecture. The Government refused to allow Catholic adoption agencies to opt out of anti-discrimination legislation which made it illegal for an agency to refuse to consider a gay couple as potential adopters. The refusal means that those adoption agencies will be forced to close or continue as privately-funded ventures. In this, highly secularist interpretation of the equality before the law principle, a body of believers who maintain, in accordance with their religious principles, that the best place for an adopted child is with a mother and a father, are precluded from offering a public service. The privatization of religion follows, and believers are herded ever more into ghettos. That has long been the experience of continental Europe, and Britain, with a long pluralist tradition in which religious and secular can both operate in the public square as equals, is fast moving now in that direction.

Dr. Williams has issued a clarion call for a vital principle in democratic law, which is that our social relations are not constituted by a single or exclusive mode of belonging. As countless papal encyclicals make clear, we are not all atomized individuals naked before the law and the state, and the law should recognize this fact. Perhaps it was inadvisable for the Archbishop of Canterbury to use the religious community which has acquired bogeyman status in the secularist imagination to make his point. But the point is the right one to make, and using the example of Sharia to drive it home has ensured that at least people have sat up and listened, even if they prefer not to hear.