Science/Tech

Emancipate the Embryo! Britain set to enter ‘brave new world’

British Members of Parliament must decide this month on a vast range of ethical issues contained in the Labour Government’s most far-reaching shake-up of fertility and embryology legislation in almost 20 years. The awesomely complex ethical issues raised by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology (HFE) Bill will be hotly contested when its body parts are voted on at the end of this month. On Monday, the bill passed successfully through the Commons after three hours of heated – but also thoughtful – discussion, but many of the MPs made clear in their speeches their determination to resist parts of the bill at later stages.

The bill brings together a formidable alliance of supporters: the Government, the scientific establishment, the pharmaceutical corporations, liberals and the Left, as well as most of the media. Yet it is striking how little press coverage has been given over to the ethical issues involved. Editors know that most of their readers simply don’t have time or interest to engage with topics that usually belong only in ethics textbooks. There is not so much an ethical deficit in Britain as an ethical gaping hole.

Resisting the bill is a determined but internally divided pro-life coalition of Catholic and Anglican church leaders, evangelical Christians, pro-life MPs of all parties, and prominent Conservatives. Hampered by an inability to agree on common strategies and outcomes, they have been focusing on different parts of the Bill that they think are winnable.

Catholics, starting with three members of the cabinet (including the transport minister, Ruth Kelly, an Opus Dei supernumerary) have led the rebellion within the governing party: most of the 60 Labour MPs—less than a fifth of the total of 315—opposing the bill are Catholic. Earlier this year they forced the prime minister, Gordon Brown, to back down from his earlier insistence that the vote would be whipped. Now MPs will be able to vote with their conscience at least on the bill’s most contentious clauses.

But the prominence of Christian opposition – underscored by prayer vigils outside Parliament and the strong condemnations of bishops - has allowed the bill’s supporters to frame the issue as one of religious conscience versus science. The head of the fertility watchdog, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, recently accused the Church of using “fatal” dogma to oppose all forms of research on embryos and most IVF treatment. Because the Church opposes all embryonic research, Lisa Jardine argued, its opposition to allowing animal-human hybrids embryos should be discounted.

The bill’s proponents are scientists backed by the pharmaceutical corporations who are pumping billions into stem-cell research, benefitting from the permissive environment which has made Britain a leader in the field. They have been largely successful in persuading public opinion of the future promise of such research. That does not mean British people are comfortable with the means. Cardinal Keith O’Brien of Scotland captured the feelings of many in his Easter homily when he condemned what he called “experiments of Frankenstein proportion” on human embryos. But appealing to the revulsion many people feel at the proposal to mix human and animal DNA is unlikely to be enough to dispel the soothing reassurances from the medical establishment that embryonic stem-cell research opens the way to cures for debilitating conditions such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

The HFE bill itself does not include abortion but seeks to update and liberalise the regulations governing the manipulation of human embryos, in two main areas: medical research, and fertility clinics. But pro-lifers are taking advantage of the opportunity to table an amendment to bring down the legal upper limit for abortion from 24 to 20 weeks, a move backed by the Conservative Party leader, David Cameron, and resisted by the Government.

The reason for the Bill

The Government’s justification for the bill is that scientific developments have raced ahead of the provisions of the 1990 HFE Act. The aim of that Act was to allow basic research on human embryos and to regulate the fertility clinics offering in-vitro fertilisation. Although the 1990 Act fell short of recognizing the embryo as human life – which it could hardly have done, given the abortion law – it accorded the embryo a “special status” and imposed constraints: human embryos should be used only if the research was justifiable; and only embryos younger than 14 days could be used – before the “primitive streak” develops, the nerve tissue that is the first indication of the capacity for thought. Having established the broad regulatory framework, the Act handed over the day-to-day regulation of the IVF industry to the body it created, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, which includes an ethics subcommittee made up of representatives of the IVF industry and just one church voice – the ultra-liberal Anglican Bishop of Oxford, Richard Harries.

The HFEA has been the object of heavy criticism from both pro-lifers and the IVF clinics themselves, both of whom complain that its rulings are reached in secret, without proper consultation, and are opaque and contradictory.

Most of the problems have arisen with ethical dilemmas posed by technology which the 1990 Act did not anticipate. Shortly after the act was passed, “pre-implantation genetic diagnosis” enabled IVF clinics to select embryos with particular characteristics. At first the technology was used to filter out genetically defective embryos. This was in itself controversial: disability rights groups, for example, objected. But the same technology could also be used to detect eye colour and gender. Applications from fertility clinics to do this were rejected by the HFEA’s ethics committee; yet it has, controversially, allowed embryos to be selected as “saviour siblings”. At least two embryos have been allowed to be selected because they contain a particular tissue compatible with that of a brother or sister suffering from a serious medical condition – in other words, a baby genetically selected and brought into the world for the purpose of assisting another human being in the treatment of his disease. But why allow a “saviour sibling” for the good of one family, but not allow “gender balancing” – i.e. to select a girl in a family with two boys – for the good of another?

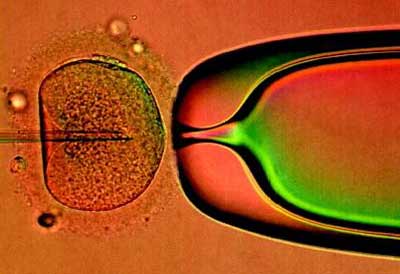

In embryo research, meanwhile, technology has already taken the scientific research into territory unforeseen by the 1990 Act. In 1996 the birth of Dolly the cloned sheep launched a world-wide effort by scientists to clone human embryos that would allow stem cells to be harvested for medical research purposes. The 1990 Act had spoken of the human embryo, but struggled to extend that meaning to that of a cloned embryo. Was a cloned 14-day year old embryo a human embryo? No one was sure. In 2001 Parliament allowed cloning, but made clear that a cloned embryo could not be implanted in a woman, and must be destroyed after 14 days.

Calls have mounted for Parliament to reassert control over these ethical dilemmas. Yet MPs themselves need guidance. Some have argued that the only way Parliament can possibly be well-enough informed to regulate embryo research and fertility technologies is by creating a National Bioethics Commission. In 2005 the Archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor, sought the Prime Minister’s backing for the idea. Citing models successfully operating in other European countries, the Cardinal suggested that the Commission would be authorized by Parliament, and be both authoritative and representative. Scientists and fertility experts would argue with moral theologians and ethicists, and publish in-depth papers which would be used to brief parliament and the press. Such a body, the Cardinal argued, would deliberate properly in full public hearings, thus avoiding the ad hoc, secretive, and often bizarrely inconsistent modus operandi of the HFEA.

While the Government has resisted that call, it has acknowledged the mounting demands for parliamentary oversight. Hence the HFE Bill now before Parliament, the fruit of a consultation with the medical establishment whose priorities it reflects. In this way, the Government hopes to side-step a wider ethical debate, keeping firmly at bay the opposition of the “unscientific” pro-lifers and neutralizing growing public unease.

What the Bill proposes

The bill allows for the creation of human-animal embryos, known as hybrids or chimeras, for research purposes. Harvesting stem-cells from cloned human embryos is already legal, but not the mixing of human and animal sperm and egg. The bill will allow the creation of hybrids (50% human and 50% other species) as well as cybrids (99.9% human) for use in laboratories, with the condition, as ever, that they are destroyed after 14 days. But as David Albert Jones, bioethics lecturer, points out, the fact is that “an embryo is always an embryo of something: a human embryo, a pig embryo, a chimpanzee embryo, etc. In law and ethics we treat embryos of different species differently. The question is, what species is a true hybrid embryo?”

The call to allow hybrids comes from the medical research lobby, which argues that this kind of experimentation is vital to future research. (Notice the Wellcome Trust’s sponsorship of the objective-looking discussion on the bill on the London Times’ online pages.

This is nonsense. So far all the breakthroughs in stem-cell research have involved the ethically uncontroversial use of adult stem cells, not ones harvested from human embryos. And no scientist is currently asking to create hybrids. Lord Robert Winston, the fertility pioneer, admitted recently it was “no great shakes” if scientists were not allowed to engineer hybrids. “The last 20 years,” says David Albert Jones, “has seen increasing momentum in favour of allowing more and more bizarre kinds of experiment for less and less reason.”

The momentum comes from the furious lobbying of the pharmaceuticals and Britain’s largest charity, the Wellcome Trust, which funds much of the research. Who has the authority to disagree with the lobby that insists it must have the freedom to explore all options so that at the end of the road miracle cures will be available? Only the scientists themselves, and few have been willing to raise their heads above the parapet. Many privately say the arguments of the lobby are highly questionable, but are afraid to speak out because their institutions would lose the huge grants on which they depend.

Yet last year even the Government’s Chief Medical Officer acknowledged the unease among scientists, describing the hybrid embryos as a “step too far”. Liam Donaldson admitted to a parliamentary committee last year that some scientists felt a “degree of repugnance” at the idea. “It was felt… there was no clear scientific benefit; there was no clear scientific argument as to why you would want to do it, and, secondly, a feeling that this would be a step too far, as far as the public is concerned.”

So the Government is pushing through a Bill that will allow experiments about which there is considerable public unease and for which there is no real demand from scientists. If the HFE Bill tells us anything, it is that there simply is no longer a culture of life in wider society capable of withstanding determined lobbying by corporate-backed research institutes.

Church leaders have been calling, in vain, for proper public debate. The Catholic Archbishop of Cardiff, Peter Smith, asked recently whether hybrids will be “human, animal or something in between” and warned against rushing into something that had not received public attention. Rejecting the charge that the Catholic Church’s dogmatic opposition to all embryo research disqualified it from participating in the debate, Archbishop Smith said the questions the Bill raises are just as relevant to people without faith. The question, he said, was about what it is to be human and how human life should be treated. But that is one debate too deep for the current British climate.

The bill introduces a number of changes to fertility regulations, effectively rubber-stamping decisions by the HFEA. The first gets rid of the requirement for a father. The law is currently ambiguous on the topic: it encourages fertility clinics to consider the need for a father before giving couples access to IVF, but the law is held to be discriminatory against single women and lesbians and is not being applied. Both sides want to make the provisions unambiguous: the bill seeks to alter the requirement to a need only for “supportive parenting”, while opponents want to make access to IVF treatment explicitly conditional on there being a father. According to a leading Conservative, the bill “hammers a nail into the coffin of the traditional family” and leads us even further in the direction of the “fatherless society”. This is one part of the bill which the Government is at risk of losing.

The other change is intended to put to rest the controversy over “saviour siblings” by allowing it. The bill permits the screening-out of genetically defective embryos—indeed bans the deliberate selection of embryos that carry disabilities (thus preventing deaf parents, for example, from selecting a deaf child.) But it allows the selection of an embryo that grows into a child with a particular tissue type, if the family needs that tissue to help treat a sibling with a particular disease.

This raises the question of the commodification of human life. Writing last Sunday, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, noted that in most people’s understanding of what counts as moral behavior, it is taken for granted that you don’t use anyone else just for your own purposes – or even for other people’s purposes. “A human person, an individual body with feelings and thoughts, needs to be treated, as we sometimes say, as an end in itself, not a tool for someone else’s agenda. So we condemn rape, torture and blackmail. We don’t allow experiments on people’s bodies or minds without their consent. And we don’t breed human individuals to create a pool of organs that could be transplanted to save the lives of others.”

The Catholic Archbishop of Cardiff, Peter Smith, issued a similar warning. If the bill becomes law, he said, it would bring into the world children “who may be loved, but who have been born in order to be donors”.

Abortion: a chance for review

Britain currently has one of the most liberal abortion laws in Europe, allowing women to terminate abortions up to 24 weeks into their pregnancies. There are currently 200,000 abortions a year, a third of these carried out by women who have already had an abortion.

A series of opinion polls over the past three years have shown growing public disquiet at the numbers and frequencies of abortions: two-thirds of doctors, two-thirds of the public and three-quarters of all women favour a reduction in the legal upper limit.

This is partly because, 40 years after the 1967 law which made abortion legal, a generation of women has seen or experienced its consequences; partly because ultrasound technology has made the humanity of the fetus more vivid, leading to a new empathy with the unborn; and partly because premature babies can now survive outside the womb at 22 or 23 weeks (although this remains rare).

A series of amendments on cutting the abortion limit will be tabled this month as the Bill passes through the house: some call for a reduction to 22 or 20 weeks, others for 16 or 13 weeks. The Conservative leader, David Cameron, is backing the call for a 20-week upper limit being proposed by an MP and former nurse, Nadine Dorries Because the 1967 Abortion Act drew the line for legal abortions at the age of fetal viability – the age in which a baby can survive outside the womb – she is arguing that the success of premature babies at 22 or 23 weeks now makes a change in the law necessary. But her evidence is strongly disputed.

The pro-life groups, not untypically, disagree on what kind of a reduction they want to see. Although the Catholic bishops have agreed on a “gradualist” approach, seeking a step-by-step restriction abortion law, the Society for the Protection of the Unborn Child opposes any attempt to change the law via amendments to the HFE Bill, arguing that any restriction will be offset by the liberalising of access to abortion. They may be right: the Conservative health spokesman, for example, thinks the legal limit should be 22 weeks, also believes but the law should be changed to allow abortion on demand. Other pro-life groups simply favor a reduction, not specifying.

Some 18 different groups – mostly of Catholic and evangelical inspiration, mostly small outfits – have united to oppose the HFE Bill in a campaign called Passion for Life. But it has failed to make much impact in the media. The pro-abortion and pro-embryo research lobbies are far more powerful, far better organized, and use sophisticated, well-funded PR techniques to get their message across – and in the case of abortion can count on cadres of committed feminists and socialists.

But the pro-Life movement also has to ask itself where it is going wrong. More than 50 percent of people oppose the creation of hybrids, two-thirds of the population want there to be fewer abortions, and there is deep unease about “saviour siblings”. Fewer than 10 percent of the British population go to church, so this is not, despite appearances, a disagreement between religious people and secularists – despite these being the voices most often heard in the debate. Yet the pro-Life movement is seen as an essentially religious lobby, for whom embryos have souls and for whom abortion is above all about sin. The fact that the pro-Life movement has been unable to capitalize on the widespread unease at the further erosion of respect for human life should cause it to reflect not just on its aims and strategies, but on its inability to connect with wider public opinion.

An hour before the second reading in Parliament, on Monday this week, I stood with a small crowd of about 30 outside the Commons. We sang hymns, and an evangelical pastor asked for a miracle, because humanly, he said, this bill was impossible to defeat.

That is almost certainly true – now. But humanly (and human activity is, after all, fertile territory for the Holy Spirit) there has been much, much more to be done.

Global warming may have awoken our society to the degradation of the globe, but it was the growing human consciousness of the preciousness and vulnerability of the environment which has made us all Green.

Can the same now not be done for the unborn, the human-life-in-being, the embryo in the laboratory dish – a campaign that does not demonize the lab-coated researcher, but awakes him to what he is really tampering with?

FREE THE EMBRYO! It could just catch on.

By AT 05.21.08 02:11PM Not Rated

It seems we need a lot more prayer:

Cow-human cross embryo lives three days

April 03, 2008 01:38am

Human-cow embryo created in world-first experiment

Embryo survives for three days

Critics say development is ‘monstrous’

HUMAN-cow embryos have been created in a world first at Newcastle University in England, hailed by the scientific community, but labelled “monstrous” by opponents.

Full story:

http://www.news.com.au/story/0,23599,23476268-38200,00.html?from=public_rss

By AT 05.21.08 11:18PM Not Rated

This leads to some very interesting questions. What is the status of this hybrid, spiritually? Would it have a soul? Or would it just be a mindless beast with some human aspects? Of course, that then leads to the question of the nature of animals, and the possibility of their salvation.

By AT 05.22.08 02:37PM Not Rated

Actually, this “hybrid” would never reach maturity as a living “beast”... with today’s technology. Don’t go looking for man-cows anytime soon. Do be on the lookout for destruction of human beings in the name of power, prestige and selfish desire.

I believe this kind of work begs other questions; Are there things men should not consider? When have we crossed a line from searching for truth to arrogance? Have we lost our trust in Divine Providence to the point of allowing anything in the name of preservation?

By GTN AT 05.20.08 07:42PM Not Rated

I’m glad to see Britain finally getting back into these issues. I’d like to see some real changes back to Christian principles. I’ll be praying things go right.