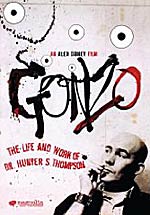

Movies

Gonzo Suicide

Gonzo should have been subtitled “The Life and Work and Death of Hunter S. Thompson,” because the writer’s suicide three years ago was the flare-out of a fading star, a premeditated decision that shrouded his last moments in existential uncertainty. Did the Lion in Winter flip a final bird to established conventions, rebel to the end? Or was it the despairing act of a lonely addict whose best work was behind him? David Griffith’s Godspy essay on Thompson included the insight: “Thompson’s decision to take his own life deserves attention because he was a great sinner… Great sinners, as Augustine has shown us, can bring us insight into the human struggle that no one else can.” Thompson’s suicide was a symbolic gesture, no question; a symbol of what, exactly, is less certain, complicated by the Gonzo writer’s devotion to self-mythmaking. He fashioned himself after Hemingway and Fitzgerald: hard-drinking, hard-living writers who wrote often about the American experience, its character, and that green light across the lake, the elusive American Dream. Like Hemingway, he ended with a gunshot to the head. Only God can penetrate the mystery of the human heart, but a quote from the Catechism seems apropos: “If suicide is committed with the intention of setting an example, especially to the young, it also takes on the gravity of a scandal.”

Was Thompson’s suicide a scandal, a symbol, a tragedy? How did Thompson himself view it? Who knows—maybe not even Thompson. As the father of his own brawling brand of participatory journalism, Dr. Thompson was never much for interiority, only subjectivity: what he saw and what he did. His brain was typically too altered to meditate on the secrets of the human soul, preferring instead his apocalyptic style of visceral, immediate reportage, as in that famous first sentence: “We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold.” Thompson’s writing lacks soul in the literal sense; at its best it’s passionate, extroverted, funny, vicious, and incisive, but not insightful, not on a deeply human level. Thompson could satirize society and authority figures, but he could rarely sympathize (except perhaps with outsiders like himself, another symptom of his self-absorption), which is one of a great writer’s most necessary qualities. If he believed in the afterlife, it was only as a blazing Inferno inhabited by the oily politicians and swinish hypocrites he loathed with such intensity. He didn’t believe in souls, only behaviors. Maybe not even behaviors, only personas. His persona won out in the end. As John Updike said, “Fame is a mask that eats away the face.”