Faith

Beyond Benedict, ‘the American Pope’

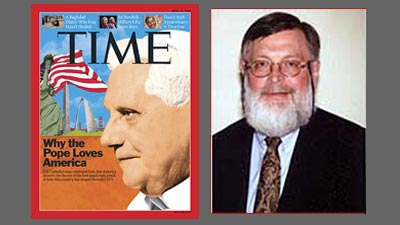

Time Magazine’s recent cover story about Benedict XVI’s upcoming visit had two headlines: “Why The Pope Loves America,” and “The American Pope.’ Neither title was accurate.

It’s hard to imagine the soft-spoken, intellectual, Mozart-loving pontiff as somehow quintessentially American. But is it true that he loves America? Sure, but in the unconditional, fatherly sense—not, as the authors of the Time magazine story claim, because “he sees us as the world’s best example” of a faith-based society. The story pieces together anonymous quotes from Vatican officials and disparate generalizations from Catholic thinkers to construct an argument that is just not supported by the evidence. In fact, the article is rife with half-truths and several flat-out errors.

For instance, it’s just plain wrong to simplistically state that a key Vatican II idea was “complementing the blind piety that prevailed in the church before the 1960s with the rationalism of the Enlightenment and thus with modernity.” Vatican II was opposed to that sort of schizophrenic Catholicism. The article goes on to state that the Church wants faith and reason to work together—that’s true—and that “The U.S. is one of the few places where it seems to happen regularly.” That’s bunk. The U.S. is where you find the two—faith and reason—most frequently at odds with each other.

Where else would both The Da Vinci Code—an example of loopy “reason”—and Left Behind—an example of kooky “faith”—be best-sellers? Where else would you find one presidential candidate (Barack Obama) supported by a preacher (Jeremiah Wright) who believes the Government is behind the AIDS virus, and another (John McCain) supported by a preacher (John Hagee) who believes that our foreign policy should be based on a bizarre interpretation of the Book of Revelation?

What we Americans are likely to hear from the Pope is a loving but clear-cut critique of our quirky combination of religion and secularism, which was precisely the theme of a Crossroads Cultural Center symposium held at Columbia University last Wednesday, titled, ‘Only Something Infinite Will Suffice,” a discussion on the teachings of Pope Benedict XVI and their relevance to American culture (The symposium was repeated with a slightly different line-up on Friday in Washington D.C.)

A quote from one of the speakers, published in today’s Washington Post, nicely summed up the symposium’s accurate take on the Pope and America: “’At the Vatican, there is an admiration for American religiosity,’ said Monsignor Lorenzo Albacete, a theologian and a U.S. leader of Communion and Liberation, a large group of Catholics that is very close to Benedict. ‘But there is a question whether American religiosity is strong enough. It appears to be, from the Vatican point of view, content-free, more spiritual high and emotion than a serious question as to what is true and what is not.’”

For a sampling of content-free American Catholic religiosity, check out today’s New York Times audio feature, “Catholic Views, Catholic Voices.” It’s a heart-warming but puzzling hodge-podge of the mostly subjective “feelings” of American Catholics that ends up signifying nothing. (Check out the most thoughtful comments, from Henry Okafar, Mila Ramirez, and Terry Sullivan). My guess is that a non-Catholic would be thoroughly confused by this mish-mash of opinion.

But back to the symposium. The five speakers were Archbishop Celestino Migliore, Fr. Richard John Neuhaus, Carl Anderson, David Schindler, and Msgr. Albacete. Each one had something significant to say—Msgr. Albacete was profound, as usual. Carl Anderson’s wonderful new book, A Civilization of Love, will be reviewed in an upcoming post—but it was Dr. David Schindler’s speech that clearly dominated the event, mostly because it went to the root of what is wrong with religion in Western culture.

Peter Maurin, co-founder with Dorothy Day of the Catholic Worker movement, once wrote:

Catholic scholars have taken the dynamite of the Church,

have wrapped it up in nice phraseology,

placed it in an hermetic container

and sat on the lid.

It is about time to blow the lid off.

This statement has haunted me since I first read it. When I discovered David Schindler’s book, Heart of the World, Center of the Church, about seven years ago, I felt this was the theological dynamite that Maurin was talking about. This was the theological approach that would mend the split between faith and culture that was confounding the Church.

Unfortunately. Schindler’s ideas aren’t easy to communicate. Since that time, I’ve been saddened by the fact that Schindler’s thought hasn’t become more well-known. But last week, while listening to his speech, that feeling returned, mostly because I had never heard Schindler communicate his ideas so forcefully, in such direct, accessible language. More important, I had a sense that the crowd was having a similar reaction. You can read the transcript of the event, including Schindler’s speech, here. It’s not easy reading, but anyone who puts the effort into understanding it will be rewarded with a much richer understanding of Pope Benedict XVI’s thought.

I’ll try to summarize as best I can here: First, Schindler says that despite the fact that “the great majority of Americans continue to believe in God and indeed to give him an important place in their lives” … in America “relation to God cannot be integrated into the logic of reason as exercised in the public life of the academy, politics, economics, or indeed morality.’ In other words, while we privately believe in God, he is absent from the important, public areas of our life.

Second, Schindler goes on to say that for the pope, we exist in relation to God. The truth we must each acknowledge is that “I do not come from myself; rather, I come from another.” God upholds our very existence at every moment, so we can never be neutral or silent about him.

Schindler’s third point, about the obligations of Christians, is very important: “...[the] desire to love God and others generously arises naturally. It is not merely a function of grace, although the desire is fully realized only in grace. The task of Christians, then, is to awaken this desire and give witness to it: to show that the restlessness driving every act of human consciousness in its depths is–even in America–a restlessness for God and for love. This is what is meant by the ‘pursuit of happiness,’ rightly conceived.”

Schindler’s fourth point is multi-faceted. I will only mention a few aspects. First—and this was the revolutionary idea from his book that first attracted me—“the search for truth, about being as love and finally about God, needs to take its place at the heart of the modern university.” This might seem obvious, but what Schindler means is different from what, say, Pat Robertson means about the purpose of a university, because he has a Catholic understanding of a God-centered reason that is open to freedom, which “respects while reconfiguring the rightful autonomy of the disciplines.” It’s the “reconfiguring” that’s key. In other words, Christians need to imbue every aspect of knowledge with the form of faith—which is trinitarian love. It’s not enough to wait until knowledge transgresses the moral law, as with embryonic stem-cell research, or cloning. Christians in pursuit of knowledge need to see all of reality as a reflection of the Trinity. Just as important, because God is reflected in reality, and is not just an idea in our heads, everyone, whether Christian or not, can come to know this reality, and Christians can share their experience of the mystery of reality with non-Christians.

In a statement that makes an important distinction about freedom, the quintessential American idea, Schindler says that for the pope the definition of freedom is “an act of love in search of God, which includes even as it transforms America‘s dominant view of freedom as an originally indifferent act of choice or exercise of options.” In other words, as St. Augustine made clear centuries ago, freedom is more about desire than it is about willpower. Freedom is not about having lots of choices; it’s about removing obstacles to our natural desire for God, and what is good, true and beautiful. I’ve always used the metaphor of a compass: a compass that was free to point in any direction would not be free. It would be broken. A compass that’s free would be free to point north, in the direction of its natural attraction.

Schindler says that while “Benedict‘s theology does not reject the distinctive goods realized in America‘s institutions,” such as the separation of Church and state, “this does not mean that he accepts America‘s achievements in their dominant present form.” Here he reiterates the teaching of the Vatican II document on religious liberty, Dignitatis Humanae. What many don’t realize about DH is that while it established religious liberty as a fundamental right, it reaffirmed that the purpose of liberty is the search for truth. The state must never be indifferent to truth, a state of affairs the pope characterizes as a “dictatorship of relativism.”

Schindler’s fifth and final point is too rich to summarize adequately here. It’s a radical statement about how the pope believes that the revelation of the cross as love is the basis of history. The pope, he says, is concerned about “a widespread assumption today–though it often goes unspoken–... that, if Jesus had had the benefit of liberal institutions and access to the Internet and so on, he could have avoided an ignominious death on the Cross.”

Instead, Schindler explains, the cross is an essential aspect of human experience. To make the case for the universality of the cross, Schindler quotes the pope’s startling reference to a quote from Plato: “…according to Plato the truly just man must be misunderstood and persecuted in this world; indeed, Plato goes so far as to write: ‘They will say that our just man will be scourged, racked, fettered…, and at last, after all manner of suffering, will be crucified…’ This passage, written four hundred years before Christ, is always bound to move a Christian deeply.”

Schindler ends by saying that Pope Benedict is calling America to “a new sense of the reasonableness of God- and love-centeredness–in short, of the call to holiness–and consequently a new sense also of the reasonableness of the demand for openness to God and to love precisely at the heart of America‘s public culture.”

This makes clear Benedict’s paradoxical challenge to America – to embrace the “reasonable” proposal that the God who is love is also the God who is love crucified. It’s the same challenge the pope is presenting to the entire world, especially the West, which is why in the end the difference between America and Europe is small compared to the grand task they both face.

That task was best summed up by Msgr. Albacete at the close of the Washingyon Post story: “’Christianity is stronger here than anywhere else in the West, but we are at the frontier of the encounter between faith and modernity. If Catholics can learn how to live here in a way that is reasonable and human and compassionate, it will be a great example for the church. Will we be up to it, I don’t know.’”

By Dave AT 04.14.08 07:57AM Not Rated

What would we do without Lorenzo Albacete?