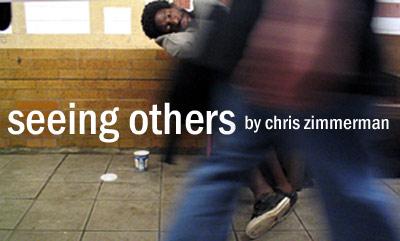

Seeing Others

“I am an invisible man,” Ralph Ellison once wrote, “simply because others refuse to see me.” Ellison was writing, of course, as an African American. He lived and died in Harlem, and spent his life agonizing over the way his people were not just beaten down, but passed by and ignored. I see Ellison’s words every time I pass them on the marble slab of his memorial on 151st Street, not far from my house. But it’s only after living in his neighborhood for a year and a half that I’ve begun to let them sink in, and to realize how often my blindness makes others invisible to me.

I’m not just talking about blacks, or about racism. Their suffering remains invisible enough, most tellingly in Jena, Louisiana, though also in a hundred other places. So is the invisibility of the working poor in general, at least in a large city like New York, where no one but those who have to ever venture into the most rundown blocks. If you’d go, you’d see all sorts of things hidden from the view of most Americans.

Last winter an elderly couple across the alley heated their apartment by turning on all the burners on top of the stove. Last week, a friend of mine visited a dying woman whose apartment is pitch dark, because Con Ed turned off the power, and she can’t get to the corner store for a candle. In the early morning you might see an unemployed Latino immigrant curled up under a stairwell, bundled against the rain, the rats, and the passersby who told him to get a job. Or the prostitute hiding behind a sidewalk scaffold, covering her face with one hand and shooting up with the other. Or the troubled young man who calls himself Nicole, lying on the park bench he calls home. Few tourists know about the Rikers Island bus, which lurches toward the prison through the post-industrial wasteland of northwestern Queens packed with silent, grim-faced mothers who won’t give up on their loved ones, even if they’ve been making the same trek for years.

But there’s another kind of invisibility closer to home. It’s the invisibility of the ordinary people we meet every day but subconsciously shut out of our lives because of their views. Often we do this on the basis of a snap judgment: we meet someone (or hear about them without even meeting them) and decide on the spot that they’re not in our camp. Instead of listening to them and finding out what makes them tick, we hold them at arm’s length and weigh their every word.

Some people close their minds as soon as they learn the source of an anecdote or the politics of the person they’re talking to. Sometimes they turn off as soon as they find out what the person does for a living or whom he or she hangs out with. Plenty of socialists hate cops (and plenty of farmers hate animal-rights activists) merely because they’re cops and animal-rights activists. Some progressive Catholics won’t associate with born-again, right-wing Protestants, and vice versa, even though both claim to follow a Christ who loves everyone. Women who speak out are called feminists, or worse, and women who don’t are presumed to be oppressed. People who voted for Bush are excoriated by those who didn’t, while those who question foreign policy are tarred and feathered as supporters of terrorism. I could go on, and so could you.

Sometimes it seems like every personality-type has been compartmentalized. Take sexual orientation, for instance, since it’s always making headlines. A generation ago, it wasn’t something you discussed at dinner. Today no one-at least no one in the public eye-can get by without some sort of label: straight, gay, lesbian, bi, trans, or in between.

On a personal note, I know someone who won’t talk to her parents or siblings because they differ on abortion and the war in Iraq. Then there are my children, who have been called “nigger lovers” because they’re the only whites at their school. (On the flip side, I myself have been accused of being a “mother-f-ing undercover cop” while walking in my mostly black neighborhood at night.)

Important life issues are often divisive, and the convictions we form when we argue over them won’t always lead to a drink at the same bar. In fact, they may lead us to opposite sides of the barricades. But what’s the point of wasting energy perpetuating mean-spirited stereotypes about your adversaries? Why does everyone need to be either a selfless hero, or an unregenerate villain? Surely there must be normal, middle-of-the-road people struggling somewhere in between.

It doesn’t help that most of us have unlimited access to information, and can bolster almost any argument with a quick trip to the Internet. In an age when everyone’s an expert on every issue, it’s easy to arm yourself with the right data (culled from websites and newswires you’ve decided are trustworthy) and jump into the fray. But our endless gathering and regurgitating of information has not made us any wiser than our parents. Indeed, it’s probably made us deafer to the voices of the real, live people around us. And because we don’t allow ourselves to hear their stories and struggles, we’ll never be able to ask them what the world looks like from their point of view.

Why is it that we so often pass up chances to have a heart-to-heart encounter? Why are we so hesitant to respect the soul of the person in front of us, and so quick to disrespect it by labeling him or her, and walking away? One common problem is plain old arrogance. When you come face to face with someone (or a whole group) whom you’ve previously written off or rolled your eyes at, it takes humility to discover what you have in common. With humility, a person you regarded as an opponent may turn out to be your brother.

In his short story The Encounter (1932), Heinrich Arnold writes, “A man should seek a true encounter with everyone he meets. By that I mean a real understanding of what is deepest in that person. Such an encounter will not vanish with time, which is fleeting. It will remain; it has lasting value. Every person we meet is an opportunity to come closer to truth. I have missed so many chances… Who is our neighbor whom we are supposed to love as ourselves? That question is two thousand years old. The answer is clear. It is the first needy person we meet… It is this walking past the suffering of our fellow human being that makes us so hard-hearted.”

In a similar vein, the poet Longfellow once wrote that “if we could read the secret history of our enemies, we would find in each person’s life sorrow and suffering enough to disarm all hostility.” Strangely, it is the very consciousness of pain-including the travails of others-that sometimes divides us. And those of us who take up “good causes” on behalf of others are especially susceptible. Instead of learning compassion (the Latin means “to suffer with”), we too easily end up self-righteous and shrill, and instead of enlarging and opening our hearts, we let the earnestness of our battles get the better of us, and defend and fortify ourselves with walls.

Thousands of years ago, the prophet Isaiah foresaw the day when a Messiah would come and heal all the wounds of his fractious society, and ours. “Then shall the eyes of the blind be opened,” he writes, “and the ears of the deaf unstopped.” Most of us probably think of blind and deaf beggars when we read these words. In fact, they describe what must happen to each of us as we work toward a world where no one is invisible, and we learn to truly listen to each other, and truly see.

By AT 06.03.08 01:30AM

A thoughtful, beautifully written article. As I get older, I have come to appreciate the commonality of human experience. We are so quick - too quick—to label others.

By AT 06.07.08 09:03PM

Thank you so much for writing this. I think we all need to be reminded from time to time that our lives are not measured by how good we are at silently condemning others. Great article.

By AT 09.24.08 05:22PM

Very moving article, reminds me of Martin Buber’s “I and Thou.” Thank you and cheers to you and your vision!

By Withouthavingseen AT 04.01.08 02:22PM

Mr. Zimmerman,

I think toward the end of your very well-written article you get to the heart of what leads us to see through others, rendering them invisible. I want to clarify that point and repropose it while drawing Christ into its core.

We are each wounded and our wounds are painful. Those wounds don’t quite heal over, except in the warm tenderness of Christ. Otherwise, they only scar, become very hard, and yet somehow still sensitive from time to time. Hardened over and forgotten, our wounds become sources of pain - woe to him who even inadvertently bumps into one of our sore spots - that we can’t quite trace. Something hurts, but we are only vaguely aware of it and have no clue why, so long ago has the wound been buried and forgotten. Like a splinter that we never let our Father remove, it becomes infected.

The vision of a vulnerable or visibly damaged other is an unpleasant reminder of the wounds we have suppressed from our consciousness and (we think) from our self-presentation to others. In reality, our wounds ooze and everyone but us (or perhaps more bitterly wounded souls) can tell that we are angry, hurt, fearful, desperate. Our wounds ooze these things and we think that continuing maintenance has fixed the problem. A homeless beggar, someone we know to be undergoing major psychiatric intervention, a retarded woman at church, a humiliated prostitute, a war amputee - all these people make us uncomfortable because we are uncomfortable in our own wounded skin.

Jesus Christ, the Divine Physician, alone can heal our personal, internal wounds and divisions, which healing is a precursor to any genuine interpersonal, external wounds. We live in a marvelous age with all kinds of modern miracles that people frankly no longer trust. We cling to them for lack of anything better; yet, nobody really expects psychiatry alone, politics alone, economics alone to make them better, to heal them. As a result, our world is becoming desperate.

This is what the late John Paul the Great of blessed memory and our current Holy Father have been telling us: now is the time to cast into the deep, seeking that deep interior healing upon which all transformation in Christ is based; now is the time to seek holiness so that we can show the world is a new way; now is the time to proclaim the Resurrection of Jesus Christ Crucified. We must proclaim him in words of love and in deeds of mercy. When we do, a hungry, thirsty, wounded world will begin to reorganize itself around Christ, and implicitly against the powers that have divided and enslaved us.

Thank you for your thoughtful article.